The New York Times Obituary of E. Gene Smith 12/28/10

July 21, 2011 2:17 pm UTC

By MARGALIT FOX

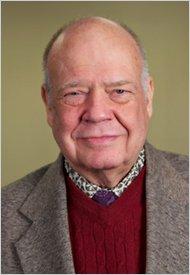

E. Gene Smith, a Utah native who through persistence, ardor and benevolent guile amassed the largest collection of Tibetan books outside Tibet, saving them from isolation and destruction and making them accessible to scholars and Tibetan exiles around the world, died on Dec. 16 at his home in Manhattan. He was 74.

The cause was not known, but Mr. Smith had had diabetes and heart trouble in recent years, said Jeff Wallman, executive director of the Tibetan Buddhist Resource Center, which was founded by Mr. Smith and a small group of friends in 1999.

Now at 17 West 17th Street in Manhattan, the center houses nearly 25,000 books dating from the 12th century. Besides containing many of the seminal texts of Tibetan Buddhism, the collection comprises secular works on a range of topics.

Mr. Smith, a scholar who became so enamored of Tibetan culture that he converted to Buddhism as a young man, was renowned for his seemingly limitless knowledge of Tibetan literature and his equally limitless fervor for saving it.

The center has begun to digitize its collection, making the texts accessible (in the Tibetan language and script) to anyone with Internet access. Almost 14,000 volumes — more than seven million pages — are available on its Web site, tbrc.org, which receives more than 3,000 visitors daily.

“The idea is to deliver the tradition back to the owners of the traditions,” Mr. Smith told the Buddhist magazine Mandala in 2001.

Though Mr. Smith had neither an academic affiliation nor a doctorate, wherever in the world he happened to be living — in New Delhi, where he acquired Tibetan literature for the Library of Congress; Cambridge, Mass., where he started the resource center in his house, sleeping amid towers of Tibetan books; or New York — his home became a magnet for students, scholars, religious leaders and exiles who sought his expertise on Tibet’s rich but little-known literary canon.

“The value of Tibetan literature is two things,” David Germano, a professor of Tibetan studies at the University of Virginia, said last week in a telephone interview. “First of all, it’s one of the four great languages in which the Buddhist canon was preserved.” (The others are Chinese, Sanskrit and Pali, an extinct language of India.)

“In addition to the scriptural canon,” he said, “there were histories, stories, autobiography, poetry, ritual writing, narrative, epics — pretty much any kind of literary output you could imagine. So the second value of the Tibetan canon is it’s one of the greatest in the world.”

The canon was imperiled after China invaded and occupied Tibet in the 1950s. Though fleeing refugees managed to smuggle some books out, the Chinese destroyed a great many others.

“With the close of the Cultural Revolution, you essentially lost much of the Tibetan Buddhist literature,” Professor Germano said. “It was lost to the war; it was lost to the destruction of the monasteries, libraries and collections of books in Tibet that were systematically sought out and burned during the Cultural Revolution.”

Ellis Gene Smith was born on Aug. 10, 1936, in Ogden, Utah, to a Mormon family that traced its lineage to Hyrum Smith, the elder brother of Mormonism’s founder, Joseph Smith.

After attending a series of colleges, Mr. Smith settled in at the University of Washington, where he studied Mongolian and Turkish, earning a bachelor’s degree in Far Eastern studies in 1959.

Around that time, as he began work on a doctorate at the university, he started studying Tibetan with a visiting lama, Deshung Rinpoche, and was entranced. Further study was hindered, however, by the lack of available texts.

“We had no Tibetan books,” Mr. Smith told The New York Times in 2002. “Deshung said: ‘Go and find them. Find the important books and get them published.’ ”

After advanced study in Sanskrit and Pali at Leiden University in the Netherlands, Mr. Smith went to India in 1965, spending several years studying with exiled Tibetan lamas. He joined the Library of Congress field office in New Delhi in 1968, eventually becoming field director there.

Mr. Smith acquired as many Tibetan books as he could for the library, seeking out Tibetan refugees in India, Nepal and Bhutan and earning their trust. Most of the books he collected were either hand-lettered manuscripts or had been printed in the traditional manner, using carved wood blocks. (Tibet had no printing presses.) Often, a book he obtained was the only known copy in the world.

In India, Mr. Smith began printing new copies of thousands of Tibetan books. He was aided, serendipitously, by a United States program, Public Law 480, which let developing countries buy American agricultural commodities in local currency. The United States would take that currency and invest it in local humanitarian projects.

As Mr. Smith noted, nothing in the law expressly forbade using the money to republish great works of literature. And so, book by book, he brought much of the Tibetan canon to light. His publishing project, which lasted two and a half decades, furnished books to libraries and Tibetan speakers around the globe, greatly augmenting the store upon which scholars could draw.

“Without his vision, many of us in the field would not be doing what we’re doing,” Leonard van der Kuijp, a professor of Tibetan and Himalayan studies at Harvard, said last week.

In later years, after the Library of Congress sent Mr. Smith to Indonesia and then to Egypt, he continued collecting and publishing Tibetan texts through intermediaries. He retired in 1996 and three years later founded the center, where he served as executive director until last year.

Mr. Smith is survived by three sisters, Rosanne Smith, Carma Wood and LaVaun Ficklin.

He was the author of several published catalogs of Tibetan literature and a volume of essays, “Among Tibetan Texts: History and Literature of the Himalayan Plateau” (Wisdom Publications, 2001).

“Digital Dharma,” a documentary film about Mr. Smith and his work, is currently in production.

Interviewers often asked Mr. Smith what propelled his quest. His answer was simple, and Buddhist to the core:

“Karma, I guess.”

Copyright 2010 New York Times